Idaho: Bataan Mountain Bike Ride

“You won’t find the Bataan Death Ride in any mountain bike guide on Sun Valley.”

Hilliard, Bataan Death Ride

“The snake was mud brown, a foot long and with its black reptilian eyes and incessant forked tongue, looked mildly dangerous.”

“It’s a matter of pride

to nonstop the Bataan from bottom to top. Riders often quit at

the first hairpin.”

“And then, when it seems as if my heart, lungs and legs can give no more, the Bataan miraculously levels out and the ridge opens to spectacular views of the Wood River Valley.”

“Somewhere below,

a large rock waits on the road to catch me tucking behind the bars.”

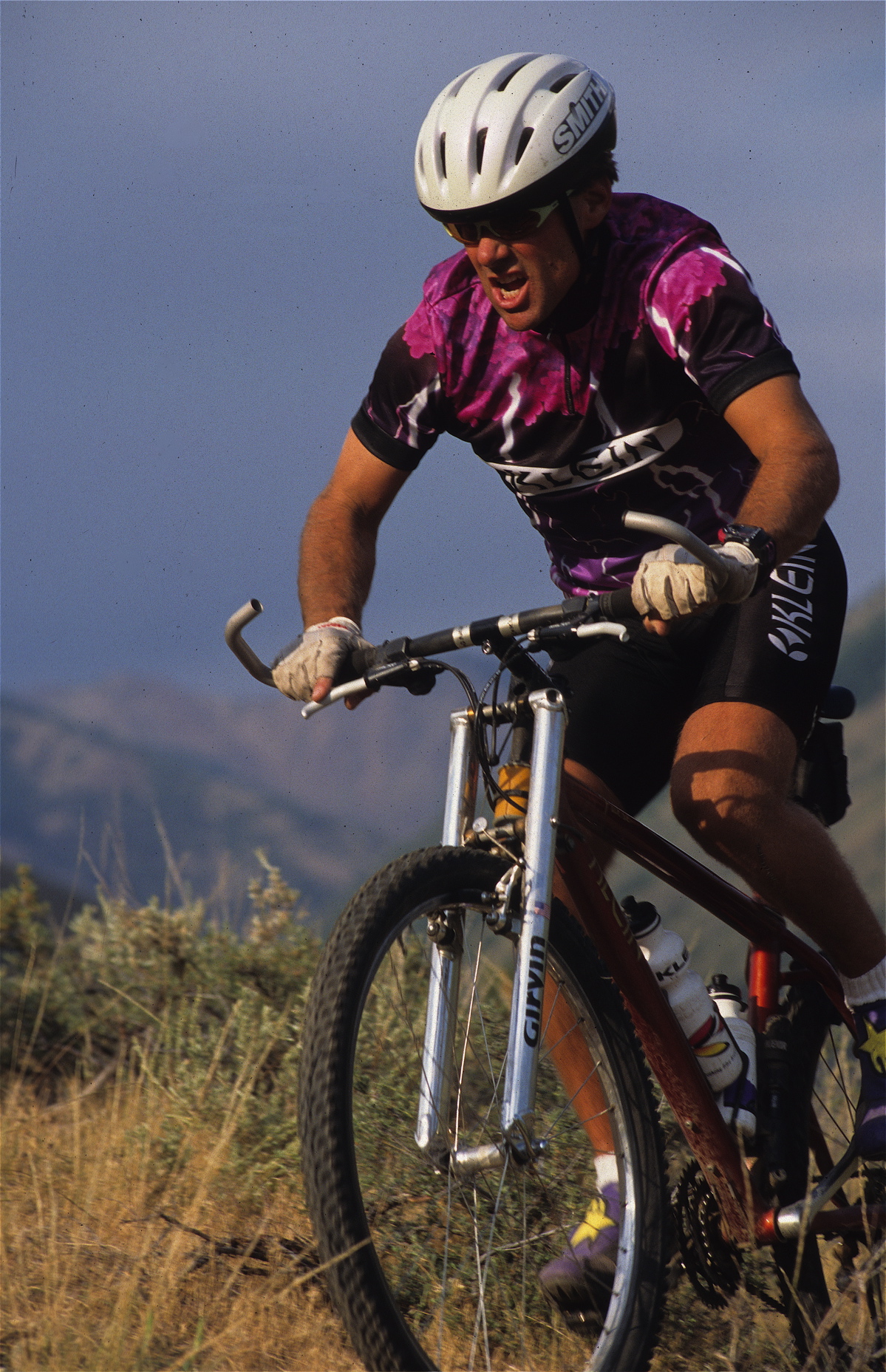

You won’t find the Bataan Death Ride in any mountain bike guide on Sun Valley. There are reasons, however, why this old mining road evokes the notorious World War II Bataan Death March. First you must consider the 1100 vertical feet in one mile grade. Next add a thigh smoking, back burning, oxygen debt, redlining, half hour climb to a distant ridge. Then, if that sounds excessive, unless you’ve got the big guns–buttocks like cannonballs, hamstrings as thick as bridge cables, cordwood for thighs and massive striated calves, this ride will do you dirty.

Even Rich Fabiano–a great Italian Locomotive of a man who takes a visceral pleasure in crushing his friends, suffers on the Bataan. Lesser men walk the last stretch, while many never make it beyond the first hairpin. For those who live to suffer in a dark anaerobic well where time stands still, the Bataan may be well something less than the Ride to Hell. But for mere mortals made of flesh, bone, sinews and brains, riding the Bataan in early spring is akin to being broken on the inquisitor’s wheel. Halfway up this ride, even the innocent are ready to confess to sins real and imagined.

To get to the Bataan you must first ride into the face of the Devil’s Bedstead. Because the Bataan climbs a tributary canyon of the East Fork of the Wood River, this old mining road emerges from the snow in mid-April. Unlike bluebirds, butterflies or other winged creatures that herald the coming of summer, the Bataan appears as little more than a gravel track that turns off North Star Road, beyond the old mining town of Triumph.

The Bataan is strictly a training ride–a way to condition muscles, joints and the cardiovascular pump for daylong mountainous enduros. Here you will not ride through dark fir forests, or through fields of wildflowers or be forced to cross clear streams. It is an unrelenting grind up a shale track that turns upon itself half a dozen times.

I’ve only seen one woman on the Bataan. She was a mix of blonde hair, striated sinew, tanned muscle and sweating determination. Lost in a sea of her own endorphins, she managed half a smile, then, lowering her head, returned to reefing on her peddles.

Because the first two hundred yards of the Bataan can be ridden in a 42/22 alpine sprocket, I always go out fast to the first turn. At that point, the grade increases and I’m driven into my 32/22. Here, where the Aspens shade the road and the Magpies mock me as I rise to the peddles, there is no rest and I try to think of something other than the distance to the ridge.

In the past I have watched deer study me from the hillsides, heard Chukar Partridge call from the shale and almost run over a dark brown snake laying across the road. Lost in the no man’s land between my hammering heart and burning lungs, a snake did not immediately seem so odd. It was only after I’d ridden a hundred feet further uphill, that something seemed distinctly out of place and turning around I laid the bike down, sank to my knees and proceeded to sweat on the unmoving creature.

The snake was mud brown, a foot long and with its black reptilian eyes and incessant forked tongue, looked mildly dangerous. I later tried to find it in a guidebook on Sun Valley wildlife, but aside from Garters, Bulls and the occasional Rattler, snakes do not do well at 6000 feet. I have since concluded it was an Idaho Asp, a lethal descendant of Cleopatra’s executioner. Such a snake belongs on the Bataan and I prodded it with a stick until it slithered reluctantly back into the sage.

Half a mile from North Star Road, the Bataan passes a weathered miner’s cabin. During summer, squatters kick the packrats out, set up a ring of aluminum chairs and settle back to enjoy the good life. They are a rough unshaven bunch, who pass a bottle of bourbon around as I labor by. I’m glad none ever wave or say hello or, out of general neighborliness, invite me over for a pull off their bottle. Either way I’d be in trouble. If I accepted or, if I refused, I’d never make it to the ridge.

For that reason, even though the Bataan grows dramatically steeper, I’m pleased when the cabin disappears behind me. By now I’m in my lowest stump puller. On flat ground, it feels as if I could climb a tree in this gear and yet I’m down to 50 RPMS and stare expectantly through the sweat to where a rusty water pipe emerges from an old mine shaft. Following a wet winter, a crystalline stream of water pours from the pipe to erode pools on the road. Crossing the channel flings a stripe of mud up my back but by now I’m beyond caring.

It’s a matter of pride to nonstop the Bataan from bottom to top. Riders often quit at the first hairpin. At that point they can see the ridge and, with their thighs howling, sense the worst is ahead. From the hairpin, the Bataan traverses across an open face toward the Triumph Mine’s crumbling buildings and rusting stamps. In February of 1917, an avalanche roared through the bunkhouse of the nearby North Star Mine killing 17 men. Today the sheer sides of the canyon are stained with dark shafts, gray tailing piles, broken machinery and an old wooden cistern that sits out on a point above a dark purple lilac.

Passing this proliferate shrub, I wonder who planted it. A wife or sweetheart of one of the miners? Or perhaps, in attempt to bring a bit of color to his bleak existence, the miner himself. It helps to think about the lilac’s origins for it is here that my heart soars through its redline. Employing the formula for maximum heart rate, mine should be 180. But on this shale grade the monitor I wear beeps like a cardiac smoke alarm warning of an impending melt down.

Wood River Valley

And then, when it seems as if my heart, lungs and legs can give no more, the Bataan miraculously levels out and the ridge opens to spectacular views of the Wood River Valley. To the north Elkhorn and Sun Valley give way to the distant Boulder Mountains which rise like battlements of a weathered Rhine Castle. To the west, Bald Mountain is ringed by a labyrinth of runs, shining lift cables and the sun reflecting off the Seattle Ridge Lodge windows.

It is not wise to linger over the view. On the downhill you cool off quickly. Better to forge ahead to where the Bataan drops precipitously into Independence Gulch which in turn connects with the Sun Valley bike path that returns to East Fork. Or alternatively to turn around, drop the shifters into high and grab a handful of back brake.

From here back the Bataan serves as one high speed blast toward the distant valley. Somewhere below, a large rock waits on the road to catch me tucking behind the bars. A brittle image of flying over my front wheel to a grinding crash counsels caution. As the speed comes up and the tears stream from my eyes, I silently pray some four wheeler isn’t creeping toward the next blind corner. I tell myself one Bataan Death Ride per week is enough. At the same time, it occurs to me if one is good, two must be better. Only not tomorrow.